History of Adoption

Adoption as it is known today is a relatively new phenomenon, based on European and American legal and cultural definitions of “family”. Other cultures have different views about adoption. Some do not believe it is possible to emotionally or socially terminate parental rights; however, other societies and cultures practice their own forms of substitute child care if a parent is unable or unwilling to parent. It is important to consider the ways these practices have influenced and shaped current adoption and permanency practices by examining the history of adoption in the United States.

Responses to children without parents

Responses to children without parents have varied. Historically, children’s placements have included:

- Boarding and indenture situations

- The church or religious institutions

- Orphanage and asylums

- Baby farms

- Orphan trains

- Native American boarding schools

- Foster homes

- Adoptive homes

From the mid-1800s through the 1920s there was a growing understanding that children were vulnerable. During the Progressive Era in the United States, a concern about child protection and safety emerged. At the same time, child placement was as much about “civilizing” and assimilating what many thought were troublesome ethnic populations as it was about child protection.

Views of childhood and children

Prior to the mid 1800’s, Children were valued for their economic contribution to the family, not for their emotional contributions. Children were seen as little adults and were expected to work at a young age. Children were not seen as a vulnerable population needing protection. It was a common practice to place children with extended relatives, particularly when families were poor. Child labor laws to protect children from being exploited and exposed to harsh working conditions were not fully passed until 1938. In fact, there were no laws that protected the physical safety of children until the case of ten-year old Mary Ellen Wilson in 1874. Because there were no child abuse laws, animal cruelty laws were used to argue for Mary Ellen’s removal and protection from the extreme physical and emotional abuse inflicted by her adoptive parents. It wasn’t until 1960’s that Dr. Henry Kempe created The Battered Child Syndrome.

Mary Ellen Wilson

Photo credit: New York Times, 2009

Progressive Era (late 1800s – 1930s)

From the mid-1800s through the 1920s there was a growing understanding that children were vulnerable. During the Progressive Era in the United States, a concern about child protection and safety emerged.

ca. 1890s, New York — Three homeless boys sleep on a stairway in a Lower East Side alley.

ca. 1890s, New York — Three homeless boys sleep on a stairway in a Lower East Side alley.

— Photo by Jacob Riis, Image © Bettmann/Corbis

At the same time, child placement was as much about “civilizing” and assimilating what many thought were troublesome ethnic populations as it was about child protection.

Boarding and indenture:

Children would sometimes be loaned out to other families where they would work in exchange for room and board. These placements were economical, not placing a child for affection and nurturance.

Sometimes parents would place children within religious institutions, particularly churches, where they would work in exchange for room and board.

Photo of a 12-year old cotton factory worker

Photo of a 12-year old cotton factory worker

Photo credit: E. F. Brown -Library of Congress

Baby farms

“Baby farms,” in which parents could pay a fee to have someone else take their infant, operated in the U.S. until around the 1920s. Sociologist Viviana Zelizer reports that the mortality rate reached 85-90% at some baby farms.

Orphanages

While children’s asylums and orphanages were a system of handling large numbers of children in poverty, the term “orphanage” has always been a misleading way to describe institutional care for children since the majority of children in orphanages had one or more living parents who were unable to care for them, usually because of issues of poverty.

New England Home for Little Wanderers in the 1910s. From the Adoption History Project at University of Oregon

New England Home for Little Wanderers in the 1910s. From the Adoption History Project at University of Oregon

Orphanages were thought to be a model of efficiently caring for large numbers of children. Asylums and orphanages were always intended to be temporary placements – where children could get their basic needs met until family could establish financial stability.

In the mid-1800s, particularly in urban cities like New York, the influx of immigrants led to an overflow of children homeless or placed in orphanages. Concerned humanitarians began to look for ways to reduce the number of poor children left to fend for themselves.

Orphan Trains

The Orphan Train Movement was one such project. Hundreds of thousands of children were sent by train from big urban cities in the east and placed in foster and adoptive families in farming communities from 1853 to 1929. The phrase “put up for adoption” comes from children being “put up” on train platforms for adults to choose from them to foster or adopt.

Photo: Kansas Historical Society

Photo: Kansas Historical Society

Charles Loring Brace, a Presbyterian minister who founded the New York Children’s Aid Society, started the Orphan Train Movement.

Charles Loring Brace

Charles Loring Brace

New York Children’s Aid Society ,Founder, Orphan Trains

Brace targeted children from immigrant populations that he viewed as unfit or dangerous and documented his views in his book, The Dangerous Classes of New York. Brace wrote “thousands are the children of poor foreigners, who have permitted them to grow up without school, education, or religion. All the neglect and bad education and evil example of a poor class tend to form others, who as they mature, swell the ranks of ruffians and criminals…who become the ‘dangerous class’ of our city” (p. 28). Social workers were largely responsible for ending the orphan train movement whose concerns about the treatment of children in these placements included a lack of home studies and follow up on how the children were faring. Social workers were also focused on prevention, with assistance to children and families through supports like the Mother’s Pensions for widows so they could afford to keep their children.

The majority of the children placed from the orphan trains were not legally adopted. Most children were indentured and chosen to work for families looking for older children who would be able to help economically which is why few babies and infants were placed on orphan trains. We were still in the time period of our country that saw children for their economic, not sentimental value.

Social workers were largely responsible for ending the orphan train movement whose concerns about the treatment of children in these placements included a lack of home studies and follow up on how the children were faring. Social workers were also focused on prevention, with assistance to children and families through supports like the Mother’s Pensions for widows so they could afford to keep their children.

http://www.twincities.com/news/ci_6931904

http://www.twincities.com/news/ci_6931904

The Orphan Train Movement was one way that the United States attempted to assimilate children from populations thought to be un-American. The Native American boarding schools were another way. While orphanages were being dismantled in favor of fostering, indenture and adoption, the boarding schools continued to grow and spread around the country for Indian children. Beginning in the mid-1800s, hundreds of thousands of Native American children were taken from their families and placed into boarding schools run by the government or religious institutions.

Native American boarding schools

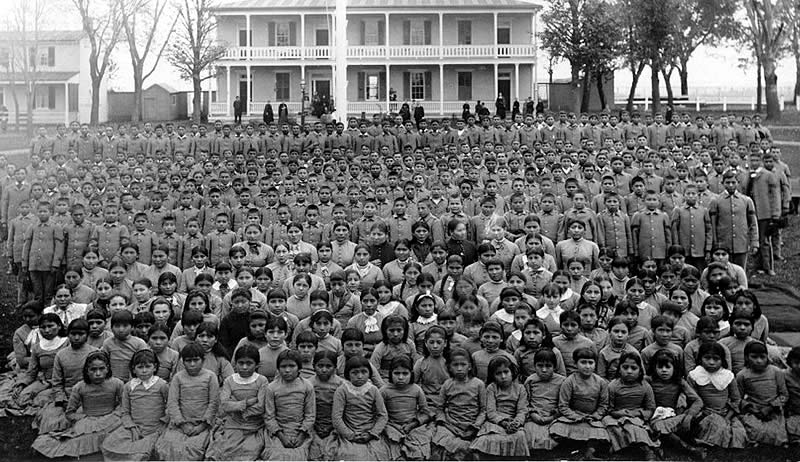

Photo of children at the Carlisle Indian School, the first Native American boarding school

Photo of children at the Carlisle Indian School, the first Native American boarding school

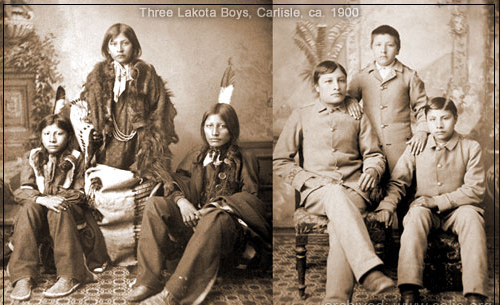

At the boarding schools, children were prohibited from wearing traditional clothing or hairstyle. They were punished for speaking tribal languages or practicing their spiritual traditions. They were forced to have Anglicized names.

Image from the American Indian Issues: An Introductory and Curricular Guide for Educators:

Image from the American Indian Issues: An Introductory and Curricular Guide for Educators:

http://americanindiantah.com/

Assimilation weakened Indian communities by ensuring future generations would not be able to continue their language, traditions, customs, spiritual practices and governance. Many children were abused and neglected in the boarding schools and most experienced trauma. Captain Richard Henry Pratt, the military leader who opened the first boarding school, Carlisle Indian Industrial School, stated “if you kill the Indian in [the child], you save the man.” Boarding schools no longer cared for children once they reached their 18th birthday. Some tried to return to their tribal communities but were unable to assimilate yet they were still discriminated against by European Americans because of their race. The Native American community still struggles with the lasting effects of the widespread removal of their children, and calls this practice of assimilation programs “cultural genocide” and have resulted in generational trauma, passed down through families and communities.

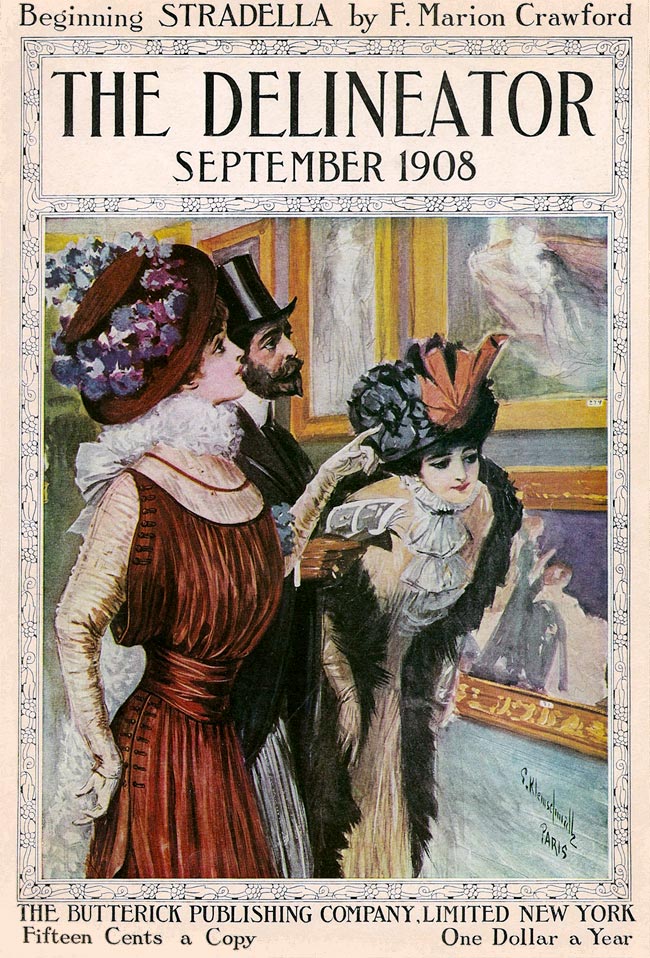

Child Rescue Campaign

Around the same time the orphan trains were running, there were other efforts to increase fostering and adoption. One of the most public efforts was The Delineator magazine’s “Child Rescue Campaign.” From 1907 to 1911, the popular women’s magazine wrote monthly articles about adoption and featured profiles of children.

In one adoption article the author wrote that “women had the future of society in their hands” through raising good citizens (Berebitsky, p. 128). 300 women wrote to the editor requesting to adopt the children profiled in the story.

The Child Rescue campaign posed adoption as not merely a solution to a social problem but as a way to fulfill women’s emotional needs to be mothers.

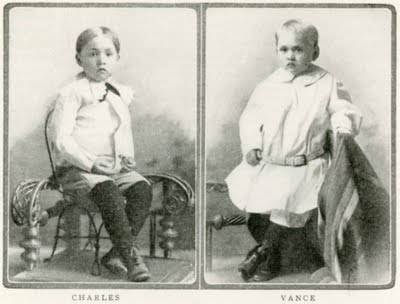

In October 1907 the magazine published a story titled “The Child Without a Home” and the story appealed on emotion and rescue – “deprived of a mother’s love, they were a potential threat to society.” The Delineator popularized the use of the child profile that is still commonly used today to inform people about children waiting for adoption.

The “two little faces who look into yours” as written in the periodical, are those of Charles and Vance, who were listed by the Michigan Children's Home Society St. Joseph, Michigan, May 2, 1908.”

In the aftermath of the Great Depression and the end of World War II, new values about adoption emerged. The Child Welfare League of America began publishing their “Standards for Adoption Practice” in 1938 to help social workers and child welfare professionals consider best practices in adoption. An increase in family building after World War II led to a greater interest in adoption as couples who were unable to conceive children biologically turned to adoption. Adoption was beginning to be seen less as rescuing children and more about family building. Adoption was also seen as the solution to infertility

Physical resemblance, intellectual similarity, and racial and religious continuity between parents and children were preferred goals in adoptive families” An emphasis was placed on “matching” infants to physically and intellectually resemble their adoptive parents. This practice was believed beneficial because adoption still carried social stigma for both the child and the adoptive parents. Since the majority of adoption agencies catered to middle-class, married, white couples were challenged by infertility; the demand for adoptable infants was high. Children of ethnic minority communities, children with disabilities, or those who were older were considered “unadoptable.” As historian Ellen Herman wrote, by matching children to parents, “physical resemblance, intellectual similarity, and racial and religious continuity between parents and children were preferred goals in adoptive families” so that it appeared a biological relationship, erasing the child’s former history.

While matching children in adoption was the practice, there were some notable exceptions:

- Native American children were still actively removed from their families and placed into boarding schools, experiencing forcible assimilation.

- The Child Welfare League of America additionally created the Indian Adoption Project, a program that placed Native American children with White adoptive families, also for the purpose of assimilation. The project ran from 1958 to 1967, placing nearly 400 children.

Other adoption practices that promoted similar beliefs about adoption as a replacement for a biological family include:

- sealing adoption records and original birth certificates

- de-identifying information about the child’s biological family

- issuing amended birth certificates with the adoptive parents named as biological parents

- the practice of closed adoptions where biological parents did not have future access to the child they placed for adoption.

Maternity Homes

Maternity homes were originally created as a rehabilitative resource for unmarried pregnant women. Most maternity homes were operated by religious organizations as a place where unmarried pregnant women would receive parenting and job-training skills so they could support and parent their child. . Parenting the child was the end goal of the maternity homes. Adoption was not the preferred option for women in maternity homes until social work professionals began to staff and manage the homes. According to Regina Kunzel, a historian of the maternity home era,whereas the previous thought was that unmarried pregnant women were victims of unscrupulous men, now the victims were the children of sexually immoral women.

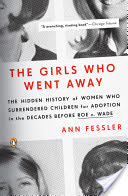

This was the beginning of the negative views about birth parents. Ann Fessler’s book documenting first-hand accounts of women’s experiences in maternity homes reveals the deep shame, stigma and pain that these women felt. Many of the women felt they had no choice but to place their child for adoption because of the pressure they received by their families and communities.

Historical perspectives 1950s-1970s

Starting in the 1950s widespread social activism such as the civil rights, feminist and disability rights movements began to impact attitudes and practices in adoption and permanency.

The focus on protecting children once again emerged when Dr. Henry Kempe wrote The Battered Child Syndrome in 1962. His book garnered attention toward child abuse, and as a result, foster care placements increased as many more children were removed from abusive and neglectful homes.

A protest of 15,000 people gather in Harlem, March 1965 (Library of Congress)

A protest of 15,000 people gather in Harlem, March 1965 (Library of Congress)

Protesting for the Equal Rights Amendment. Photo: Bettmann/Corbis/AP Images

Protesting for the Equal Rights Amendment. Photo: Bettmann/Corbis/AP Images

The placement of children with disabilities into institutional care was challenged during this time period as well, as parents began to advocate for support to raise their children. A 1972 expose of Willowbrook State School in New York revealed the abusive and horrific living conditions in institutions, prompting de-institutionalization.

The impact of Roe vs. Wade, along with the availability of birth control and a lessened stigma on single motherhood, led to a decrease in the number of infants placed for adoption. The civil rights movement also influenced adoption. As a response to the Native American boarding schools and the Indian Adoption Project, the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 was passed to allow tribes jurisdiction over placement of Native American children.

The National Association of Black Social Workers advocated against transracial adoption of Black children into White homes in a 1972 position statement.

Women who were residents in maternity homes formed a group called Concerned United Birthmothers (CUB) to support other birth parents who had lost children through adoption.

International Adoptions

Intercountry (also known as international or transnational) adoptions began right after World War II. The first children adopted to the U.S. were from Germany, Greece and Japan. The next groups of children adopted internationally were from South Korea in the 1950s, and Taiwan and Vietnam in the 1960s and 1970s. Many African American and other ethnic minority children and families were excluded from mainstream adoption and permanency services. In the 1950s, the National Urban League created a program called Adopt-A-Child, reaching out to Black and Puerto Rican communities for adoption. At the same time, some white families began to seek adoption of children of color. The first documented transracial adoption of a black child into a white family occurred in 1948 in Minnesota.

Since the 1980s we have seen some significant shifts in how we view and practice adoptions.

There has been an increased focus on “special needs” adoptions.

- The term “hard to place” was changed to “special needs” in order to lessen the belief that some children were unadoptable.

- Federal incentives such as adoption subsidies were created to help increase the adoption of children with special needs.

- Special needs includes characteristics that may hinder a child’s adoption such as the child’s age, race, disability or membership within a sibling group.

Special attention has been focused around prioritizing keeping siblings together in placement.

- Historically it was common to place siblings in separate adoptive homes. Recognition that it is traumatic for children to be separated from their siblings has led to a greater priority to keep siblings together.

Focus on reducing foster care “drift.”

By the 1990s, it was recognized that too many children were in “foster care drift” meaning they were lingering in foster care and often remaining until they turned 18, never returning to their families or being adopted. Laws prioritizing permanency were passed to reduce foster care drift and to provide children with greater security and sense of family. Concerns about the outcomes of children aging out foster care without permanency have also contributed a greater emphasis on permanency.

Along with a change in thinking about what makes a child “adoptable” there has been an expansion in thinking about what kind of parent should be allowed to adopt. Adoptive parents in the past had to be a married, heterosexual couple without any disabilities. Today, persons who are single, identify as LGBTQ, or with disabilities are adopting children yet some prospective parents still experience discrimination in the adoption process.

Since the 1980s, transracial adoptions have been increasingly more common.

- Since 1994, federal laws have prohibited child welfare agencies from delaying or denying the placement of children in foster care for adoption based on race.

- These laws do not apply to private adoptions, however many children are adopted transracially through private adoptions.

- In addition, from the 1980s until 2004 the numbers of intercountry adoptions grew at high rates.

- Since 2004 however, when over 22,000 children were adopted to the U.S., the numbers of intercountry adoptions have declined due to a number of factors.

Since the 1930s the belief and practice around adoption was to preserve privacy and secrecy. In the past few decades, there has been a significant change in this view. More and more, transparency and openness is being practiced in adoption. There has been an increase in birth parents choosing to have open adoption relationships with their child and adoptive parents. Also, led by adopted individuals, there has been activism around unsealing adoption and original birth records.

In summary, the practice of adoption today is different in some ways from how we have practiced it in the past, yet some aspects remain the same or similar. Although lessons have been learned and improvements in practice have been implemented, there remain areas of growth throughout the permanency and adoption process.